Porn and the Pope might seem an unlikely combination (or at best just bad alliteration), however within Rome’s Papal Palace lies a room full of frescoed sex scenes (Fig 1-2). Painted by Raphael in 1516, this Renaissance porn depicts Roman gods in ‘compromising’ positions. Commissioned for the private bathing chamber (Stufetta della Bibbiena or ‘small heated room’) of Cardinal Bibbiena, only a handful of people have viewed the work since its creation. Considering the content, it’s no wonder the frescoes have been kept firmly behind closed doors since their mid-19th century re-discovery.

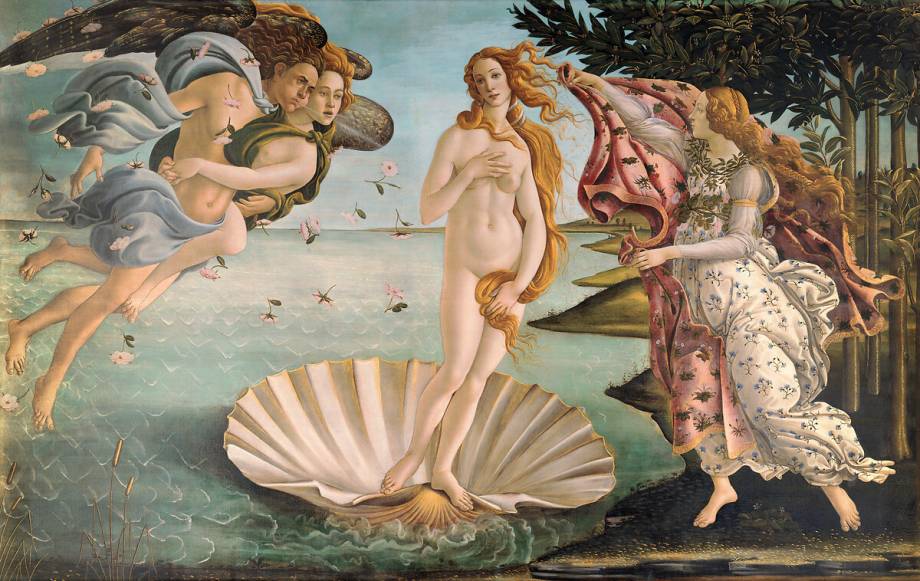

However, Tony Perrottett is an exception to this rule as he relayed his successful (albeit difficult to come by) visit in a Slade Magazine article. Together, with artistic reconstructions, the fresco can slowly be visualised. Perrottett describes the scenes of a ‘naked’ Venus ‘stepping daintily into her foam-fringed shell’; her ‘admiring herself in a mirror’ and swimming between Adonis’ legs in ‘sensual abandon’ .(1) He also acknowledges a now destroyed (and controversial) scene of Vulcan attempting to rape Minerva.(2) However, one of the most explicit and humorous scenes is Pan, the Satyr God, leaping out from the bushes with a ‘noticeable appendage’, now scratched away and replaced with eye-catching white paint.(3)

Many people know that the classical was a key aspect to the Renaissance, however you may be less aware that classical motifs were used in early forms of porn, Jacqui Palumbo describing how ‘the Greeks and Romans had imagined their gods as sexual beings, and it became in vogue to do so again in the Renaissance’.(4) Raphael was certainly aware of the sexual power of mythological images, for example, upon the completion of the Agostino Chigi Loggia (1511), he was asked by a lady as to why he didn’t paint ‘a nice rose or perhaps a fig leaf’ over Mercury’s ‘shame’(penis).(5) He replied, why had she not asked the same for ‘Polyphemus, for whom you praised me so much and whose shame is so much greater?’ (it seems size mattered from an early era).(6)

This sexual power of the classical gods most clearly manifested in the image of Venus. Where, as one of the only female figures to be painted nude, her body became a motif for sexual desire for both male and female artists (Fig.3-4 ). However, frescos, like Bibbiena’s and the Farnese ceiling, presented these sexual scenes a new format, beyond the scale of a single canvas. For example, the viewer of the Farnese ceiling could trace their eyes from the outstretched figure of Venus grasped by Triton, to Jupiter, reaching sensuously for his wife’s legs (with the erect phallic form of an eagle by his feet) (Fig. 5-6). One can imagine the impact upon the wealthy or noble male viewer as he roved his eye from scene to scene, confused by the lifelike sensuousness of the images.

Therefore, it is no surprise that the Bibbiena frescoes are linked to the first mass publication of Renaissance porn. I Modi (The Ways, 1524), also known as ‘The Sixteen Pleasures’, was an illustrated sex guide by Marcantonio Raimondi (Fig. 7). As the first published porn to be banned by the Catholic Church, and its author imprisoned by the Pope, it had a short but infamous lifetime. However, what’s relevant to us is that the work was based upon some Vatican paintings by Raphael’s pupil, Guilio Romano. These paintings, said to be a reaction to Clement VII’s late payments, were made in the Sala di Constantino, a room from Raphael’s 1508-09 commission that he left to his apprentices to complete upon his death. As Raphael completed the Bibbiena frescoes as part of the same papal commission as the Sala di Constantino, Romano possibly even helping him paint them, it’s plausible that he took inspiration from them for the Sala. Hence, rather ironically, the Bibbiena frescos inadvertently inspired the first mass publication of Renaissance Porn.

But if Raimondi’s porn was banned, then why were similar images allowed to be commissioned for the rooms of a cardinal (a supposedly celibate individual)? Firstly, Renaissance celibacy and propriety were not as serious as one might expect. Many Popes, before and after their ascension, famously did not keep to their chastity vows and had many illegitimate children, for example the Pope at the time of this commission, Leo X, was known for his relationships with men. Boccaccio parodies this hypocrisy in the ‘Decameron’, detailing the tale of two priests who ‘sported’ with a young maid, one declaring ‘no-one’s ever going to know, and a sin that’s half-hidden is half forgiven’.(8) Therefore, it is likely that Bibbiena, known for his sexually risqué plays, saw nothing wrong with ‘half-hidden’ pornography.

However, he wasn’t alone in enjoying gazing at sexual images. Whilst paintings of Venus were popular with the male patron, the previously mentioned Farnese Ceiling is especially comparable to the Bibbiena frescoes as their patron, Oudardo Farnese, was also a cardinal. Campbell suggests that these sexual works were appealing as the ‘virtue of the viewer’ was demonstrated by the ‘ability to admire the skill behind the artwork rather than give in to bodily desire’.(9) Therefore, perhaps Cardinal Farnese enjoyed the power of looking at these ‘carnal pleasures’ (as later described by Salvator Rosa), without being aroused. (10) Or maybe it was the opposite: as Bibbiena sat in his tub and Farnese stared at his ceiling, it was possibly the excitement of the forbidden that appealed to them.

The animalistic, primal nature of the Roman gods, that was in such opposition to the teachings of the Catholic faith.The Cambridge dictionary defines porn as ‘books, magazines, films, etc. with no artistic value that describe or show sexual acts or naked people in a way that is intended to be sexually exciting’. What about renaissance artworks? The explicit sexual intentions of the Bibbiena frescoes arguably make them an early form of porn. As Pietro Aretino (1492-1556) in a sonnet of the second edition of I Modi wrote: ‘Come view this you who like to fuck without being disturbed in that sweet enterprise’.(11)

Footnotes

- Perrottet, 2011

- Ibid.

- Dasal, 2020.

- Palumbo, 2019.

- Zucker, 2010.

- Ibid.

- Strike, 2017.

- Boccaccio, 1982.

- Palumbo, 2019.

- Feigenbaum, 1999.

- Strike, 2017.

Bibliography

- Boccaccio, Giovanni, Decameron (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982)

- Classen, Albrecht, ‘Sexual Desire and Pornography: Literary Imagination in a Satirical Context. Gender Conflict, Sexual Identity, and Misogyny in “Das Nonnenturnier”’, in Sexuality in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: New Approaches to a Fundamental Cultural-Historical and Literary-Anthropological Theme (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2008) <https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/32824> [accessed 27 October 2020]

- Dasal, Jennifer, ‘The Pope’s Secret Sexy Bathroom’, ArtCurious

- Feigenbaum, Gail, ‘Annibale in the Farnese Palace: A Classical Education’, in The Drawings of Annibale Carracci, ed. by Frances P Smith and Susan Higman (Washington: National Gallery of Art Washington, 1999)

- Frantz, David O., ‘“Leud Priapians” and Renaissance Pornography’, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, 12.1 (1972), 157–72 <https://doi.org/10.2307/449980>

- Palumbo, Jacqui, ‘How Renaissance Artists Brought Pornography to the Masses’, Artsy, 2019 <https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-renaissance-artists-brought-pornography-masses> [accessed 27 October 2020]

- Perrottet, Tony, ‘The Pope’s Pornographic Bathroom: My Visit to the Vatican’s Most Secret Chamber’, Slate Magazine, 2011 <https://slate.com/human-interest/2011/12/vatican-inside-the-secret-city-vatican-guide-the-pope-s-pornographic-bathroom.html> [accessed 17 October 2020]

- Simons, Patricia, ‘ANNIBALE CARRACCI’S VISUAL WIT’, Notes in the History of Art, 30.2 (2011) <www.jstor.org/stable/23208570>

- Strike, Karen, ‘The Sixteen Pleasures: The Vatican’s 16th Century Sex Guide’, Flashbak, 2017 <https://flashbak.com/the-sixteen-pleasures-the-vaticans-16th-century-sex-guide-376734/> [accessed 27 October 2020]

- Zucker, Mark J, ‘ART, SEX, AND HUMOR IN ITALIAN RENAISSANCE LITERATURE’, Notes in the History of Art, 29.4 (2010) <www.jstor.org/stable/23208976>